Carnegie Museum Retrospective of Olszewski's Art - 1993

| Introduction This section covers the 1993 30-year museum retrospective of Olszewski's 15 years of painting, and 15 years of miniature art. Here you will find reproductions of the pamphlets, brochures and a "must read" essay titled "An Emerging Art Form" written by Andrew C. Voth, Director of the Carnegie Museum in Oxnard, California from 1981 to 1994. |

Carnegie Art Museum 424 South C Street Oxnard, CA 93030 |

About the Exhibit The Art of Miniatures: A Retrospective, presents the art of Robert Olszewski, who has devoted the past fifteen years to creating a renaissance in minute sculptures of extraordinary skill, clarity and warmth.

The scale he is continuing to perfect even surpasses what can be historically considered as miniature. Inspired by the art of the past, his realistic creations are eagerly sought by collectors around the world, who appreciate the skill, beauty, style, and form he creates. In the spirit of a modern-day Carl Faberge, Olszewski has developed complex techniques required to reproduce the polychromed, bronze microsculptures.

The exhibit follows the creative career of the artist to date and includes many of his original paintings that are the aesthetic foundations for his current work. Also on display are the transitional sculptures and projects that illustrate the artist’s development into the highly refined microsculptures.

The exhibit showcases approximately 100 microsculptures, distilled down from the nearly 200 pieces he has created to date. Photographic reproduction cannot do justice to the microsculptures – they must be seen in person to be fully experienced. It is for this reason; the Carnegie Art Museum has prepared the exhibit to travel to other museums across the county.

We are pleased to present, in this premier museum exhibit, the ultimate in The Art of miniatures: A Retrospective – the amazing microsculptures of Robert Olszewski.

Andrew C. Voth, Director Carnegie Art Museum |

ROBERT OLSZEWSKI The Art of Miniatures A Retrospective The exhibit begins to your right with the painting "Fire on Presque Isle". By walking around the exhibit room in a clockwise direction you will view a chronological history of artwork by Robert Olszewski over the past 35 years. A brochure and an essay have been published for this exhibit and are free to all visitors: The brochure is a summary of the exhibit. It gives a brief history of the artist and highlights a few of his important artworks of the past The essay is written by the Director of the Carnegie Art Museum, which exhibited the first Retrospective of Robert's work in 1993. The essay is an in-depth examination of Robert's work and gives good insights into how to classify his artwork. |

|

FIRE ON PRESQUE ISLE Oil on Canvas c. 1962 Collection of Butch and Marlene Shoalts Artist Age - 17 |

THE PAINTING YEARS - 1962-1977 Robert Olszewski's interest in art was fostered by two of his art teachers in High School, and he was encouraged to pursue a degree in art eduction. While at IUP, he painted evenings and in his spare time, and developed his "eye" as an artist. Painting Plein Air - Pennsylvania Olszewski's first serious works were still-life's that were painted at night after his regular class work at IUP (Indiana University at Pennsylvania) was completed. These winter time learning exercises were abandoned when spring arrived, and Robert began painting on the spot landscapes. Each night two fresh canvases were stretched and the next morning Robert would walk until he found a new subject that interested him. |

|

STILL LIFE WITH LEMONS Oil on Canvas c. Fall, 1965 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 20

|

|

AT THE CROSSING Oil on Canvas c. Summer, 1966 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 21 |

Painting Plein-Air - California Once he arrived in California, "California light" was overwhelming. Olszewski continued to use an intense palette, painting outside, and "on the spot" landscapes. |

|

MONTECITO ESTATE Oil on Canvas c. Fall, 1966 Robert Olszewski On loan from the Collection of Mike and Joe Eichblatt Camarillo, California Artist Age - 24 |

|

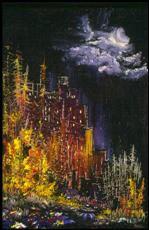

WHERE HAVE I BEEN, WHERE AM I GOING? Oil on Canvas c. 1969 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 24 |

|

FOURTH OF JULY Oil on Canvas c. 1969 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 24 |

|

LOSS OF THE DREAM Oil on Wood, Clay c. 1969 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 24 |

|

DOWNTOWN Oil on Canvas c. 1969 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 24 |

|

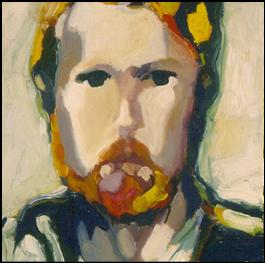

SELF PORTRAIT Oil on Canvas c. 1969 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 24 |

|

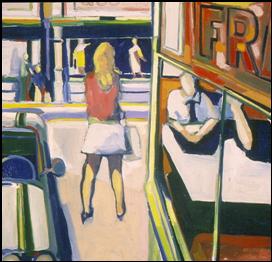

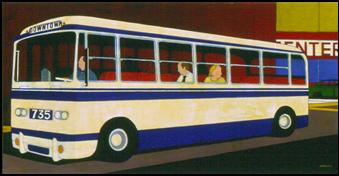

DOWNTOWN BUS Acyrlic on Bristol Board c. 1970 Robert Olszewski Collection of Mike and Joe Eichblatt Camarillo, California Artist Age - 24 |

Memory Paintings This series of works centers on important family relationships, including Grandma and Olszewski's father and brother. |

|

4 TO 12 Acrylic on Bristol Board c. 1970 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 24 |

|

PORTRAIT OF MY FATHER Acyrlic on Canvas c. 1970 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 25 |

|

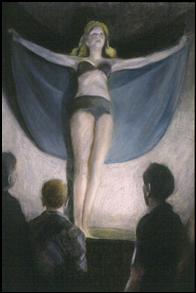

CARNIVAL SIDE SHOW Oil Crayon, Pencil on Paper c.1970 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 25 |

|

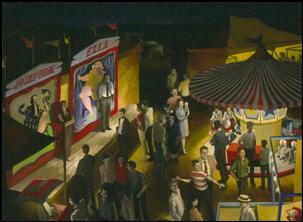

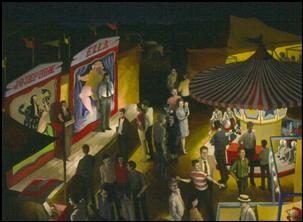

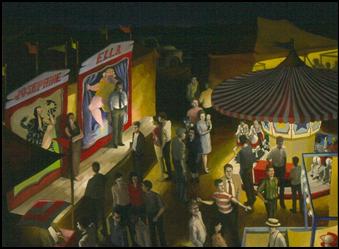

SAXONBURG CARNIVAL Acyrlic on Canvas c. Summer 1970 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 25 |

|

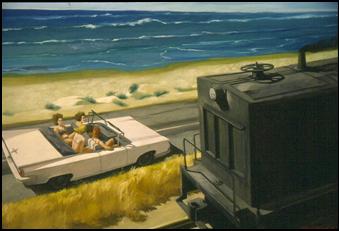

FLAT CAR WITH CONVERTIBLE Oil on Canvas c. 1971 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 26 |

The Last Painting – “Ocean Drive – 101 North” The theme of this painting was based on the period Olszewski spent at work back east earning college tuition. The beauty of the young girls Robert knew seemed so much in contrast to the environment they lived in. After his move to California Robert and his wife made many trips up the coast, and so the setting of “Work and Play” was changed to the Rincon. The softness of the girls in a white car is in contrast to the black engine, going in opposite directions illustrating the opposites, “Work and Play”. This was the last painting Olszewski completed in a painting period that lasted 15 years. |

|

OCEAN DRIVE - 101 NORTH Oil on Canvas c. 1973 Robert Olszewski Collection of the Artist Artist Age - 28 |

Carnegie Museum Retrospective Brochure

Front and Back Covers of the 12-page Carnegie Museum Brochure

|

|

The Painting Years: 1962 – 1977 Robert Olszewski’s interest in art was fostered by two of his art teachers in high school, where he was encouraged to pursue a degree in art education. While at college, he painted evenings and in his spare time, and developed his “eye” as an artist. His first serious work was with still life, painted at night after his regular class work was completed. These winter-time learning exercises were abandoned when spring arrived, and the art student began painting plein air landscapes. Each night, two fresh canvases were stretched and the next morning Robert would search the town and countryside for subject matter. The move to California in 1968 produced a change in his palette and approach to color. It also inspired the artist to reflect on the home he left behind, resulting in a series of memory paintings that allowed him to come to terms with his past. Illustrated is the painting “Fourth of July” and the sculpture “Loss of the Dream.” The flag pole represents Olszewski’ idyllic early life at his family’s country home in Pennsylvania. The painting portrays the carefree days of childhood; riding across the countryside on a bicycle under bright, sunny skies. The sculpture represents the darker side of his childhood, depicting him as a small, reflective figure in mourning over the sudden deaths of his father and a “best friend,” his dog. With this work, the stage was set for Olszewski to expand his creative abilities into sculpting as well as painting. Olszewski painted in oils and acrylics at this time, and his work was shown in several Los Angeles galleries. It is important to note the wide range of painting styles he has worked in. Not content to settle into any one technique, he continually sought to improve his skills and explore new ground. This spirit is reflected in his work today, as he continues to press the medium to its limits. After the “Fourth of July,” he continued to explore his memories, along with the use of color as a combination of light and psychological force. This series of works result in some of Olszewski’s most mature and solid works of art. His fascination with light is seen in a range of night-time subjects including the painting “The Saxonburg Carnival,” which the artist has selected as his first limited edition print. He further explores the characteristics of light in the painting “101, The Rincon,” depicting daylight.

|

Flat Car with Convertible |

|

Oil on canvas 1971, 20" x 28" Courtesy Carnegie Art Museum Collection © Robert Olszewski |

Fourth of July “…sums up nine happy years of my childhood; a childhood defined by brilliant summer skies, bike riding on a country road and the 4th of July Flag. The sculpture is an important transition work; it contrasts the optimism of the painting. This work depicts the loss of the dream. It was my first step toward becoming a sculptor.”

|

|

Oil on Canvas 1969, 34” x 36” © Robert Olszewski |

“Loss of the Dream” |

|

Oil on Canvas 1969, 34” x 36” © Robert Olszewski |

The Traditional Years: 1970-1977 A selection of papier mâché works are included in the exhibit. These were executed while he taught junior high school at Haydock, Oxnard, California. The light-hearted nature of the subject matter was a relief from the serious and contemplative paintings of self-analysis that Olszewski found emotionally challenging. Robert’s young children were a receptive audience for the “Christmas House,” which naturally progressed to a doll house for his daughter. Shortly thereafter, he commenced his work with “one-twelfth” scale figurative miniatures, or “micro-sculptures” as Museum Director Voth and his curator, Suzanne Bellah, had labeled the work. The potential of this art form became apparent to him after his first carving, “Lady With An Urn,” which he modeled after an illustration in a book of English porcelain. |

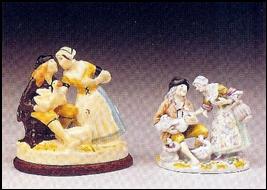

Poultry Seller “Sculpted in 1977, this early reproduction of the Meissen piece by Kandler shows my struggle with the new medium. Fifteen years later, in 1992, I re-carved and redefined the figures as an indication of how the art form has advanced." |

|

|

(left sculpture) 1969, 34” x 36” ©RobertOlszewski |

(right) 1992 3/4" ©Goebel |

|

The Autumn Blue Jay “This piece is one of my favorites. Not only does the Jay read well at a distance, but as you draw in closer to inspect it, you are confronted with the presence of the bird eyeing you. Here you are not watching passively, but are challenged to interact.”

|

|

1986 Actual Size: 3/4" ©Goebel |

The Blind Men and The Elephant “I chose to reproduce, with great respect, the spirit of historical oriental pieces. Sometimes the chosen medium was porcelain, but in this case it is ivory. Here, each blind man attempts to describe an elephant based only on his experience. One says he is like a pillar, another a snake…leaving us to understand we never have the entire picture of life but only a part of the whole.”

|

|

1986 Actual Size 1” ©Goebel |

She Sounds The Deep “The major theme of this piece is the conflict between men and the sea. During my visit to the Maritime Museum in New Bedford, Mass., I learned that whalers were separated from their families for years at a time. This stopped my complaints about business trips, and inspired my attempt to capture the peril these men faced everyday at sea.” |

|

1983 ©Goebel Actual Size 1” |

Years of Exploration: 1977-1993 The early years of Olszewski’s development and exploration were strongly influenced by Meissen figurative porcelains. It was difficult for him to find historical references to techniques and procedures, as few artists had explored sculpture on such a miniscule scale. Fully-colored (or polychrome) works in miniature were rare. Faberge and Lalique, who each worked in small scale, allowed the color of the metals to dominate. The gravitation to fully-painted and rendered finishes on a white ground was a natural evolution for Olszewski, with his experience in painting on white-primed surfaces serving as an example. In his search for an approach to the work, the final “look” and finish of the pieces has ranged from natural flat-paint finishes to porcelain-like finishes, simulating the original Dresden and Meissen figures. Other finishes include a specially patined bronze. With many years of experience in a most difficult medium now behind him, Olszewski feels that it is time to expand the emotional and creative boundaries of his art. Portraying emotion in sculpture this small and delicate is not an easy assignment. The sensitivity of Robert Olszewski’ most recent work is certainly a harbinger of even greater works to come.

|

Summer Days “As inthe “Fourth of July” painting, the recurring celebration of youth is returned to. This time the subjects are my own children. Innocence, vitality and the promise of youth are ongoing themes in my painting and sculpture.”

|

|

©Goebel 1981 Actual Size 3/4" |

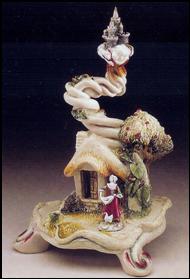

Jack and the Beanstalk “…is an old world story. And so, it has the look, feel and spirit of classic porcelain. In one look, we see Jack’s Mom looking up; waiting for her son to return. While Jack’s Mom is beautiful outside of the display she gains additional impact and mood within the context of the display. As in a painting, a character set in a two-dimensional plane is expanded by its surroundings. I am intrigued by accomplishing the same thing in sculpture. Outside of the display, Jack’s Mom follows traditional decorative sculptures. Placed inside, the total work becomes sculpture that takes on the qualities of a painting. As this concept continues to expand in my mind, I will continue to explore it.” |

|

©Goebel 1993 Actual Size: 4 ¼” |

The Carnegie Art Museum is pleased to announce the release of the limited edition print, The Saxonburg Carnival, from The Art of Miniatures, the premier museum exhibit of the works of Robert Olszewski. The Saxonburg Carnival, created to commemorate this exhibit, exemplifies Olszewski's growth as he took strides toward becoming a master artist. |

The Saxonburg Carnival “When I started The Saxonburg Carnival, I was determined to achieve the sawdust atmosphere of a Midwest carnival at night. Because this retrospective commemorates my evolution into the Art of Miniatures, I have selected this painting as my first limited edition print.” |

|

Oil on canvas 1971 25” x 34” ©Robert Olszewski |

A Message from Robert Olszewski “I have a fundamental point-of-view: the value of a work of art is not determined by its size. This concept first struck me after reproducing in miniature one of my large paintings for a police report. The original large piece had been stolen from a gallery exhibit and the police needed a photo, I reproduced it in a smaller scale. I knew after having completed the smaller work, that it was time to rethink the approach to my art. Since then, painting or sculpture, large of small scale, I have worked to define the essence of the idea that you can do great concepts in any scale, but as in all art forms, each art form has it’s assets and limitations. After 30 years of exploration, and having worked in many mediums and scales, I am certain that some things are better said in a smaller scale.”

Robert Olszewski |

The style of my paintings is very broad as the work reflects my early search for understanding my approach to painting with pieces created in high school, college and into my teaching career. The essay, "In Context: An Emerging Art Form" originally written in 1993, by Andrew Voth, to coincide with the first Robert Olszewski Retrospective at the Carnegie Art Museum is provided here. At the time the essay was written, Mr. Voth was serving as the Director for the Carnegie Art Museum, Oxnard, California. It was updated later to correctly reflect the current status of Mr. Olszewski's artwork to be used jointly with the Retrospective at the University Museum, Indiana University of Pennsylvania in 1998. After his departure from Carnegie Museum as its Director, Mr. Voth became President of Pacific Art Services, Inc, as well as Cultural Arts Advisor and Administrator, Art in Public Places Program, for the City of Oxnard, California. He also served on the Board of Trustees for Patrons of the Cultural Arts of Oxnard, and as Development Director for the Oxnard Performing Arts Center. Mr. Voth's other positions have included Director for the Pasadena Festival of Art and Science Director of Galleries and Fine Art at Ambassador College, as well as Chairman of the Art Department and Lecturer at Ambassador College, where he received his Bachelor of Arts in 1970. |

An Emerging Art Form - An Essay by Andrew C. Voth

In Context: AN EMERGING ART FORM by Andrew Voth, Director Carnegie Art Museum (1981-94) While contemplating the approach to the Carnegie exhibit, I faced a challenge. The medium is familiar and yet, different than anything I have encountered before. Could I make the bold announcement of the discovery of a new art form? Furthermore, what is the purpose of the museum exhibit for the artist, and what is really new? This essay addresses those questions and why I believe that Robert Olszewski's art should be seriously regarded as an emerging art form. An art museum is a repository and showcase for art. The media and tools of art may be, in fact, prehistoric, and yet color on canvas and sculpted forms have the ability to excite, inspire and stimulate our aesthetic senses to this very day. The art museum is also a forum for ideas-both old and new. The museum exhibit serves as the launching pad for the artist and his ideas. It is a vehicle for increasing public awareness of the art and calling attention to what is here to be viewed, experienced and absorbed. This is a serious responsibility and a privilege that brings great satisfaction to us as museum professionals. It is important to note that, due to the small (read next to Right Column top) 1 |

size of the original sculptures, the photographic reproduction of the figures cannot portray the originals with any degree of accuracy. All art suffers this transformation when put into two-dimension, but Olszewski's scale suffers it to a very high degree. The art must be viewed in person. Artists have analyzed techniques, color and form, put them through a cuisinart, totally rejected the previous generation's concepts of beauty, turned things upside down, dissected elements, cubed, chopped, slashed, splashed, impressed, expressed, annihilated, dreamed, dripped, frothed, stamped, ranted, raved, aggravated, politicized and mutilated every known media. Is there anything new today? And what is an artist to do? For a young child, and, alas, increasingly older children who have never visited an art museum, everything here is new. New becomes a relative term. The elements that strike an emotional chord in her or him, which is the essence of the aesthetic experience. This is a vital ingredient in Olszewski's work. For his subjects, he chooses those things that have touched him, whether it is his children at play, the illustration of a fairy tale, capturing the essence of a Tang horse, or a whaling party at sea. There is a story behind every piece. The paintings, which all predate the sculpture, also strongly reflect emotion. While selecting the paintings for the exhibit, Olszewski researched and found a number (read next to Left Column top) |

he had not seen in years. His excitement was considerable when he shared these with me. His exclamation “Wow, isn’t that a great painting?” did not stem from conceit, but rather from the appreciation and excitement of seeing a work of art that “has it.”. We have included as many of his paintings as possible in the exhibit. They are vital record of his training and thinking, and evidence of the range of his native talent and virtuosity. The paintings are also an important bridge to his present work in bronze, well able to stand on their own as excellent works of art. It would be most interesting to see him return to painting again. One can only wonder what direction he would take. Now, to the important matter of context. Artists have long enjoyed playing the context game, and art history is rife with ‘new” contexts. In a letter written during the mid-eighteenth century (fully one hundred years before the “Impressionist rebellion” that started when Manet, Pissaro, Jongkind and Whistler exhibited in the Salon des Refuses) Jean Baptist Chardin expressed a kindred attitude towards The Academy: These masterpieces of Greek art would not longer excite the jealousy of artists had they been exposed to the resentment of students. And when we have exhausted our days and spent lamp-lit nights in the study of inanimate nature, then living nature is placed before us, and all at once the work of the preceding years is reduced to nothing… ---Painters on Painting, Eric Potter, Editor, page 91. In keeping with this precursive “Impressionist” attitude, Chardin chose not to follow his contemporaries who went on to produce the popular paintings of the French court. He took (read next to Right Column top) 2 |

a different course and chose, not plump courtiers, but instead plump hams with pots, pans and vegetables, and ended up with a piece of art known as still life. This change of context elevated everyday items into art. Andy Warhol followed suit, some two-hundred years later, when he took a soup can out of its kitchen setting, placed it in a gallery, and called a news conference. Suddenly, a serious work of art was born. There is magic in a change of context. Olszewski has delighted in taking European porcelains, like Dresden, out of their intended contexts by creating art works in a scale not previously envisioned by anyone else. This has expanded to encompass the full array of his artwork on display in the exhibit. Some are interpretations of other artist’s works, but most are his own original creations. The technique of creating new contexts is not the sole province of the artist. Art museums have also effectively utilized the strategy. Instead of selecting items that make up a single artwork or series as an artist does, an art museum has the opportunity to take an entire body of work of an artist or trend and give it a new context. There is a transformation from viewing the figures at home and seeing them properly displayed in a museum setting. Inherent to every art form, old and new, is the power of the object to evoke an aesthetic experience. A personal anecdote: as a child of seven years of age, my parents took a family out to the Cleveland Museum of Art. The strong image of Renaissance painting, rich with a tapestry of detail and bold colors is still profoundly impressed in my memory nearly forty years later. An artist, dead for centuries, reached through time with an idea that touched me deeply. When we returned home, I looked at the “paint by numbers” set with a whole new perspective! I threw it out and obtained some real oil paints and canvas and worked to recreate the same feeling of wonder and awe that I experienced in that Renaissance painting. (read next to Left Column top) |

That first visual aesthetic experience will always burn bright in my memory. It is that same feeling by which I continue to evaluate art today. An artwork either “speaks” to the viewer, or it doesn’t. There is an immediate emotional response to the art that cuts through the encumbrances of higher education and the dulling of the senses of our life experiences. It is decidedly a right-hemisphere brain function. Art which always requires a trained docent to interpret and get the artist’s point across (if there is one) has failed as an artwork. The left-hemisphere of the brain should not have to be used to jump-start the right-hemisphere in order to create the aesthetic experience. The left-hemispherical, linear learning should augment and enrich the experience, not artificially create it. As painter Robert Henri stated: “A man possessed of an idea, working like fury to hold his grip on it…is in the hour of xpression. The only thing he has in mind is the idea alone which possesses him, and it must be expressed.” ---The Art Spirit, Margery Ryerson, page 124. This is the same energy that is felt when viewing Robert Olszewski’s artwork. It is a process of discovery and surprise to the artist, as well. When Robert calls me and says, “Wait till you see this new piece!”, I hear the enthusiasm of that aesthetic experience echoing once again in his voice. The enjoyment is not diminished upon closer scrutiny and further analyzation of his art. Olszewski has taken ancient traditional materials, and put them into a scale rarely attempted by any except the most skilled jewelers throughout history. That is the closest comparison as the historical media. However, the context and purposes of Olszewski’s art differs somewhat from that of jewelry. (read next to Right Column top) 3

|

The enjoyment is not diminished upon closer scrutiny and further analyzation of his art. Olszewski has taken ancient traditional materials, and put them into a scale rarely attempted by any except the most skilled jewelers throughout history. That is the closest comparison as the historical media. However, the context and purposes of Olszewski’s art differs somewhat from that of jewelry. I perceive the difference to be that the jeweler, notwithstanding the incredible skill involved, is preoccupied with the value of the material and the craftsmanship is worked around the precious stone as it becomes a piece of jewelry. Jewelry is generally regarded as first a “diamond and gold pendant”, or a “platinum ring with emeralds”, or a “ruby necklace in gold setting with earrings”. It is not usually described as “an exquisite sculpture set with diamonds”. The perception of precious, intrinsic value is primary to the definition of jewelry. Its context is also different. It is meant as an adornment and enhancement for the body, hopefully secondary to the person who wears it. It is also used as a portable statement of social rank among “high society”. Conversely, Robert Olszewski has taken a very lowly metal, bronze, and transformed it into elegant and remarkable works of art, based primarily on the workmanship and genius of the artist. The point being, Robert Olszewski’s art stands out whether the material is bronze or gold, embellished with precious stones, or standing alone with a simple adornment of paint. The material is secondary to the work and intention of the artist. Indeed, he has chosen to place some of his sculptures into the arena of jewelry as well, resulting in some interesting crossovers between jewelry and sculpture. It certainly seems to work and may lead to some exciting new concepts in the near future. What, exactly are these works if they are not jewelry or what we generally regard as life- (read next to Left Column top)

|

sized sculpture? They are referred to by collectors as “miniatures” and their brief history has put them into what is known as the “Collectibles Market”. This market ranges through a plethora of items including fountain pens, American glass, baseball cards, commemorative plates, porcelain figures, and antique spoons. Most “collectibles” are perceived to be in short supply or were originally created as a limited edition. Today, Olszewski figurines are produced in his private studio and in the past has been produced and marketed by Goebel Miniatures, a division of the same Goebel company that produces the popular “M.I. Hummel” figurines in Germany. Goebel is the company that encouraged Robert to achieve what he is today—no less than the world’s leading artist in a unique medium. The average collector is usually someone who was introduced to Olszewski’s work via the popular “doll house” market, where Robert first sold his pieces on his own. Other collectors are those interested specifically in miniatures, whatever interpretation that might encompass. The prices of the figures produced by Goebel are considered to be affordable by most people, and thousands were sold to collectors over a fifteen year periods. In February 1994, Olszewski established his own independent studio and though this is still the major commercial market for Olszewski’s works, there is change in the air. It has always been the artist’s realization that these are not merely collectibles, but are, in essence, real works of art that have happened to have found a successful market niche. The secondary market is confirming the increasing value of the art. The auction market is the usual real-world test form measuring this, and Olszewski’s works are fetching astronomical prices. Let us further define the medium. The dictionary states that the noun “miniature” is (read next to Right Column top) 4 |

derived from the Latin verb miniare, meaning “to paint in minimum”. However, the English language disappoints us in the extrapolated definition. The word miniature also connotes insignificant, whereas large sculpture is always referred to as monumental, with the connotation that it is more important or “better.” In discussion the nomenclature with Carnegie’s curator, Suzanne Bellah, we agreed that the term “miniature sculpture” is not sufficient to describe the medium and that a new definition is in order. We propose that the term micro-sculpture be applied. The change is not “monumental” (if you will excuse the pun) but hopefully sufficient to give us a fresh appreciation for an incredible and unique art form. The use of the word micro (from the Greek micros, meaning exceptionally small) in place of the word miniature, describes the scale of the art more accurately. It also parallel’s the age in which we live—full of microcomputers, microchips, micro-tonal music, micro-wave oven and so forth. Olszewski’s concept of the miniature-scale (now micro-scale) has been developing since 1977. He feels that each generation has created its own definition. What was considered miniature fifty years ago is not so today. He likens it to the technical advances in the computer industry. An IBM system that filled a large room twenty years ago can now be placed in a box that sits easily on a secretary’s desk or carried like a briefcase. The technical difficulties involved in creating the micro-scale are just as complex as engineering a sculpture of heroic proportions, if not more so. Technical complexity alone does not make for great art, but it does test the skill of a master. The definition of a “master” is one who has complete control of the materials he works with. Nothing is left to chance or happenstance. Occasional accidents that happen in monumental work and can be patched cannot be tolerated in the micro-scale. Any flaw in the (read next to Left Column top) |

process must be worked out or the piece is abandoned. An advantage the sculptor in micro-scale has is that he is not scrapping tons of metal with a single mistake. There are no mistakes in Olszewski’s work, as quality control is carefully monitored by him. He is obsessively concerned with what he terms visual clarity. He must get the essence of the artwork, its form, fluidity and texture for it to be a successful artwork. Part of this visual clarity is the texture and finish of each piece. And each piece is unique. The Dresden micro-sculpture has the look and even feel of porcelain. Viewers do not realize it is actually painted bronze. The micro-sculpture “ivory carvings” of the Netsuke likewise are of the bronze material, skillfully painted and glazed. The actualization of this is due to Olszewski’s background and training as a painter. He personally trains each artist that works on his editions. It takes an average of five years experience before an artist is skilled enough to paint the facial features on the micro-sculpture. He continually seeks upgrading his techniques. One figure (Lady with an Urn) executed 20 years ago recently challenged him again. “Can I improve this?” he asked himself, and then set about creating a new piece that has gone far beyond the older piece in skill and aesthetic realization. These two pieces may be viewed together in the exhibit, and the differences are clearly evident. When I asked him if he got bored with redoing a piece, he replied that is [it] was like visiting with an old friend and getting to know the friend better. It is viewed by the artist as a challenge and a way for him to measure progress in his mastery of the medium. Another element of visual clarity is emotional expression. Pushing the limits of technology, Olszewski has developed unique methods for creating eyes one-half the size of the period at the end of this sentence. Misplacing them a one-thousandth of an inch will change the entire emotional content of the artwork. The attitudes (read next to Right Column top) 5 |

of each figure must be properly conveyed, both emotional state and body stance. A flirtatious glance or a scoff is very difficult to obtain in the micro-scale. The weight of a figure resting on one foot must feel substantial. An arm in movement must feel fluid; each figure must breathe and have the lyrical content of a real person. Expanding upon Olszewski’s concept of visual clarity, the same aesthetic experience and spirit must be evoked in the micro-sculpture as when viewing a full-sized artwork. In the case of an original, it must sing its own tune and be able to stand on its own as an original artwork. The philosopher George Santayana addressed a class at Harvard nearly a century ago with regard to taste and aesthetics: Taste, when it is spontaneous, always begins with the senses…simplicity is not the absence of taste, but the beginning of it. When sincerity is lost, and snobbish ambition is substituted, bad taste comes in. The test is always the same: does the thing itself actually please? If it does, your taste is real: it may be different from that of others, but is equally justified and grounded in human nature. ---The Sense of Beauty, Being the Outline of Aesthetic Theory, George Santayana, page 50. Robert Olszewski’s artwork does please the senses. The art of miniatures is a historical record with great depth in narrow areas. Olszewski has garnered the best of these earlier art forms, widely broadened the applications, developed new techniques and made a unique statement. Although the elements he uses are not “new”, the application and scale are new. He has redefined the medium of miniature sculpture for our generation. (read next to Center Column top) |

Olszewski’s relentless energy in creating and promoting micro-sculpture, virtually single-handed, has been pursued with passion. As with other art forms throughout history, it remains to be seen how many fellow artists will attempt to put their skills to the test and join him. He will undoubtedly expand the breadth of styles, techniques and vision as times goes on. marvelous works in the same spirit as those produced by the House of Faberge are definitely within Robert Olszewski’s imagination and skill, should be choose to go in that direction. I am sure such works will be no less works of art if they are embellished with precious gems. He could also return to painting with an entirely new perspective if he so chooses. The micro-sculpture medium can expand beyond time-honored styles to encompass “contemporary” art thought and trends as well. Many possibilities open once an artist gets accustomed to thinking in the micro-scale. It may lead into entirely unexpected creative directions unique to the art form, adding a rich, new chapter to art history. No matter what future direction the medium may take, the micro-sculpture as defined by Robert Olszewski merits serious recognition as an emerging art form. .................. 6 |

Carnegie Museum Commemorative Offer

The print "Saxonburg Carnival" shown below was specifically created for the Carnegie Museum Show in 1993. Today, Olszewski Studios offers Olszewski Collectors the opportunity to purchase the print through the For Sale section. Click on image for further details. |

|

| Saxonburg Carnival c. 1971 Lithograph Artist Proofs 50 $195.00 Edition 5000 $150.00 |

All figurines and displays are copyrighted by ©Disney, ©Goebel Miniatures, and ©Olszewski Studios

info@olszewskistudios.com

Web Design By Moe Technologies, Inc.